First Published in: The Journal of the Mountain Club of South Africa

‘To call this a “classic” is almost to do it a disservice – this is THE classic hard Chamonix route! Cams and modern rockboots mean that the route can be climbed faster than it used to be but, even in the 21st Century, ticking the Walker Spur is still a major achievement.’

- Rockfax Chamonix guidebook.

‘The route is rarely dry enough to be climbed in rockboots but it needs to be if it is to bear any resemblance to this description. If you climb it in mixed conditions it will be hard and (even more) time consuming so it is best to wait (even if takes a few years) to get it when it is dry.’

After waiting for several years, in early August 2020, the Walker Spur came into condition and a quick plan was hatched with my long-time climbing partner, David Barlow. David jumped on a plane to Italy where I collected him and we headed straight for the mountain. Acclimatisation be damned! Although the route is not especially technically difficult (the hardest pitch is RSA 19), the length, difficulty of retreat, sustained nature of the climbing, abundant supply of loose rock, heavy backpacks and a tortuous, complicated descent make it a committing route requiring a robust set of alpine skills. Anyone who has climbed a long route with other parties knows that deciding on a strategy, to reduce the chance of problems with slower parties and safety factors, can be critical. When the Walker Spur is in condition, there is no shortage of potential suitors and it is not uncommon to have up to eight or nine teams starting on the same day. Most teams stay in the Leschaux Hut and then start walking in around midnight. This becomes a ‘race’ as everyone wants to be in the first two or three parties. The starting 300 m are very loose (we called this the ‘horror choss’ section) and with parties above, rock-fall is almost a certainty. Fortunately, we had a plan. Ten days prior I had walked in to attempt the route with a French mate, Edward Blanc. Just after arriving at our bivvy site below the face an unanticipated thunderstorm rolled in, pelted us with hail and thoroughly soaked us and our bivvy gear. We spent a very cold night in wet sleeping bags. Attempt over. On the positive side, it was a good learning experience as we got to see all the teams from the Leschaux Hut ‘racing’ in the morning, getting to the face and then bailing due to rock-fall and wet conditions. We needed to get ahead of them for any chance of success. Neither of us like ‘racing’ in the early hours of the morning (this is just denial – we’re both too old to ‘race’). Never mind the inevitable resulting pressure of multiple parties starting close together and the risk of stone-fall from other parties.

We chose a completely different strategy; we caught the first Montenvers train from Chamonix, walked to the route and started at about 16h00. We climbed the ‘horror choss’ section in daylight and bivvyed under a slightly overhanging wall, just below the start of the difficulties. It was, however, a most unpleasant sitting bivouac, but the overhanging wall proved enough shelter to shield us from ice and rock-fall during the night. We allowed ourselves a lie in and started climbing just ahead of the Leschaux Hut parties who were no doubt surprised and a little miffed to have been usurped for the lead. The first pitch of the day was a tad loose, but we were soon at the Rebuffat/Alain Corners, the technical crux of the route. This is steep and overhanging and proved quite challenging first thing in the morning, but we made good progress and were soon on the rightward traverse towards the ‘75 m Dihedral’. The climbing alternated between solid excellent rock to loose horror shows until reaching the ‘Grey Slabs’. This section consists of five excellent, technically difficult and sustained pitches. These bring one back onto the spur and into the sunlight for some much-needed warmth. At this point the climbing eases off but becomes gradually looser with the resultant being a rising terror level. It goes without saying that to move together on loose ground is a considerable risk and the team should be well balanced as a fall may well be fatal for both climbers.

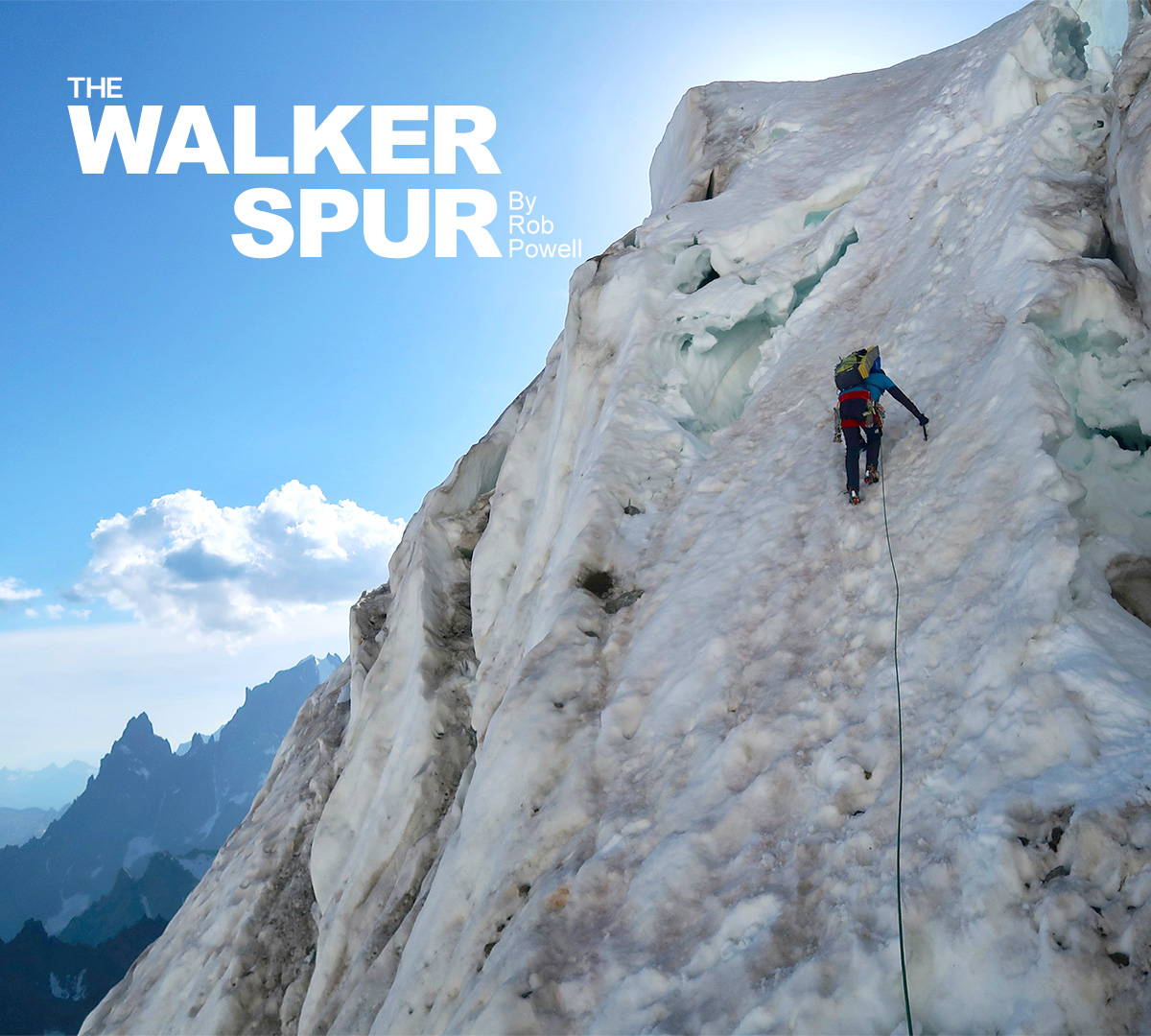

The spur gets to a choke point and we headed out left onto an ice-field (crampons and ice axe). This is followed to the end where some moderate mixed climbing leads to the base of the infamous ‘Red Chimney’. One will not forget the Red Chimney! Picture the horror choss section tilted to 80 degrees, limited protection and smeared with verglas. I think the reader will get some idea of the anxiety this pitch invokes in me when I think back on it. Fortunately, it was David’s lead, ha! We were hoping to bivvy on the summit that day and we certainly could have but after 36 pitches we came upon a flat pedestal under a big overhang in a spectacular position. It was too good to pass up and we decided to bivouac. Although it was still a sitting bivvy we could stretch our legs out and compared to our previous evening it was positively luxurious. We enjoyed a spectacular sunset in the warmth of our sleeping bags, consuming our very meagre food ration: a two-minute sachet of porridge each. The next morning was cold and very windy and after a slow start we climbed the remaining four pitches to the top of Point Walker into glorious sunshine. The descent is a route in itself, AD+ but D- if descending the Rocher Whymper. The day was warm and we thought it best not to risk the serac on the regular descent. We opted for the harder, longer but safer descent down the Rocher Whymper, the long spur coming down from the Point Whymper of Grandes Jorasses. This involves traversing the summit ridge to Point Whymper and simul-climbing down the spur of the Rocher Whymper. When it is no longer possible to down-climb, one abseils down the left side to the glacier and re-joins the normal descent route. After a short descent on the glacier one re-joins the toe of the Rocher Whymper and crosses over the right-hand side where six short abseils lead to the glacier under Pointe Croz. At this point it is reasonable to recoil in horror at the tortuous glacier and serac one must traverse to reach the Rocher de Reposoir. Once one has traversed this (and added a couple of grey hairs to one’s now extensive collection) one reaches the Rocher du Reposoir (which translates as ‘rocks of rest’) where one has the first safe and comfortable place to stop since setting off down. Here we moved together following the complex ridge down to the glacier and a long trudge down a complex and crevassed glacier to the Bocalette Refuge. The hut guardian was an absolute star, cooking us a fine Italian dinner of beef ragu and polenta which was washed down with some celebratory beers.

That left the next day to descend from the hut, hitchhike from Italy to France through the Tunnel du Mont Blanc (not an easy task during the Covid pandemic), retrieve the car from Chamonix and for me to drive David back to Turin airport for his return flight to the UK – easy! Helpful information (for those people who may be intent on climbing the route): Climbing all 40 pitches (not that one pitches it all, there is a reasonable amount of simul-climbing) in a day is a tough challenge and the descent is long and involved, so one needs to be prepared to bivvy, especially if one is not acclimatised (which one really should be).

This is what we took, which proved to be a good choice. We used almost everything and only regretted not taking more food:

• Rock rack: 1 set of wires, 1 set of cams from Red Camalot X4 to Blue Camalot 3, a mixture of 12 quickdraws and alpine draws, long slings, 1 blade peg and abseil tat – for retreat if that proved necessary.

• Ice rack: 4 ice screws (shared with our crevasse rescue kit), 3 ice axes (2 Petzl Sum’Tecs and a Nomic). We could have managed with just 2 axes, but we weren’t sure. The final part of the route can be mixed so we had to be prepared for that (with the leader taking two axes and the seconder one), but we climbed it in rock boots, avoiding the ice smears without too much difficulty. Similarly, we did the descent using only an axe each, but we might easily have needed another axe for the leader since there is one section which involves climbing a serac band.

• Comfortable rock boots, lightweight alpine boots, steel crampons. Alpine boots are needed for the glacier approach and involved descent.

• Two 60 m, 7.5 mm ropes.

• Sleeping kit: one cut in half Z-mat between us, a lightweight sleeping bag and bivvy bag each.

• One Jetboil stove with 2 small gas cylinders. Luckily each bivvy had snow or ice within reach so we didn’t have to carry any significant water up the route.

• Food: we didn’t take enough! 1 sandwich each for the walk in, 1 dehydrated meal each, 4 sachets of instant porridge, a dried soup, tea bags, chewy bars.

• Clothing: alpine rock-climbing trousers with fleece thermals for the second bivvy and the second day, long-sleeved climbing tops, mid-layer wind and warmth top, lightweight down puffy jacket, lightweight Gore-Tex top, 1 pair climbing gloves, 1 pair warmer gloves.

• The usual other essentials: harness, prussiks, knife, abseil tat, helmet, headtorch, first aid kit, phone, passport, money for the hut, Covid mask, sunglasses, sun cream, water bottle, GPS (with new batteries).

The Grandes Jorasses is a dangerous mountain. It has areas of terrible loose rock, the descent is complex and long, the glaciers are very crevassed, navigation can be difficult at night or in bad weather and there are frequent lightning strikes. Two teams were rescued off the route while we were climbing it and a skilled Italian alpinist lost his life the day before on the ‘easy’ part of the descent. Taking all the dangers into account, I must ask myself: ‘Was it worth it?’ Ten times over.

* ED1 – grade of the route, ‘Extrême Difficile’ 1

Rob Powell is a qualified South African Mountain Guide originally from Cape Town

but living in Saint-Gervais-les-Bains in France. Contact: saclimber@gmail.com